Public health is not a modern invention. Premodern towns and cities were unsanitary by our standards, but efforts to manage sanitation and monitor population health have deep historical roots. This was partly due to the emphasis of Galenic medicine on the environment.

Measures to improve sanitary conditions were initiated by governments and churches to control disease. In 1531, Henry VIII ordered the streets of Oxford to be kept clean, and for the lands around the city to be drained. In 1593, the Vice Chancellor and Mayor ordered the removal of rubbish and pigs from Oxford streets. To slow the spread of plague, they also banned plays and games. Large academic events were often cancelled due to pestilence.

During the Great Plague of 1665, the University and City issued ‘rules and orders’ to Oxford residents that are reminiscent of modern lockdown laws. No one was allowed ‘to visit or converse’ with infected persons, and feasts and ‘publick Meetings’ were banned. Finally, a watch was set up ‘to keep out infected persons’, as well as anyone arriving from London.

In 1621, the first Physick (later Botanical) Garden was established in Oxford on land belonging to Magdalen for the cultivation of medicinal plants. Such developments were accompanied by the publication of remedy pamphlets, like that written by Thomas Willis in 1666.

Another possibility was to turn to God in repentance. On 25 April 1723, a day of ‘publick thanksgiving’ for ‘our deliverance from plague’ was held at Magdalen, where a fellow delivered a sermon on Galatians.

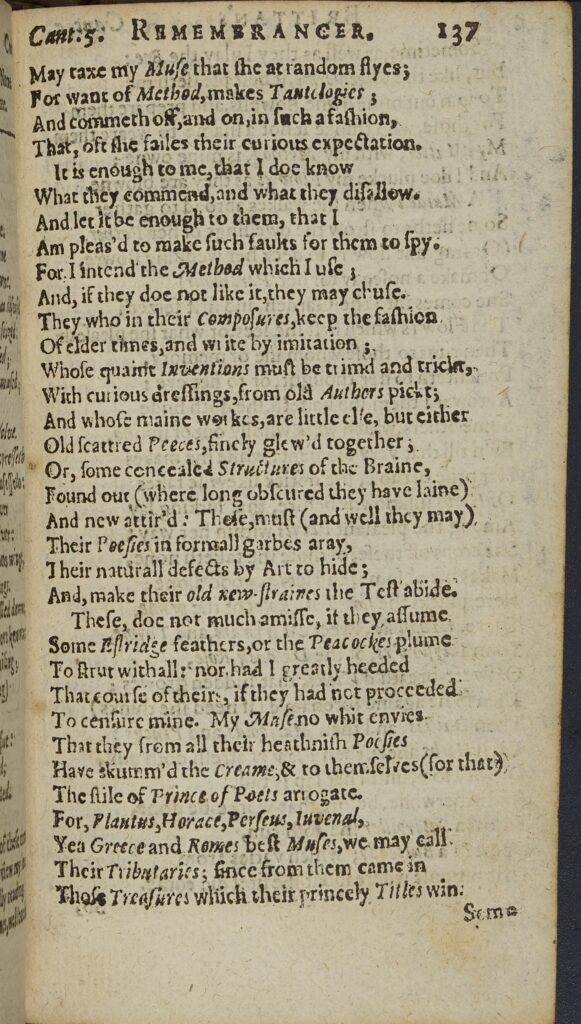

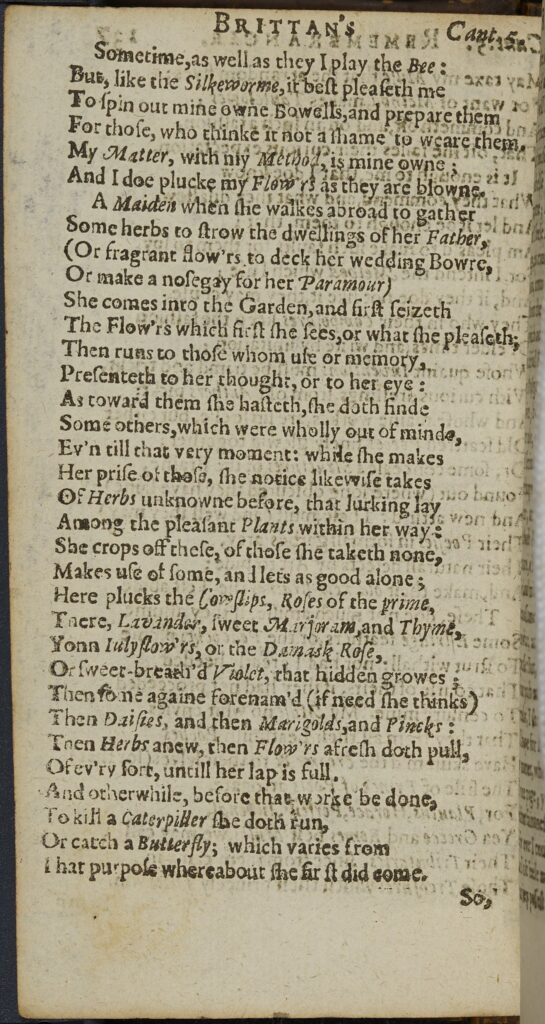

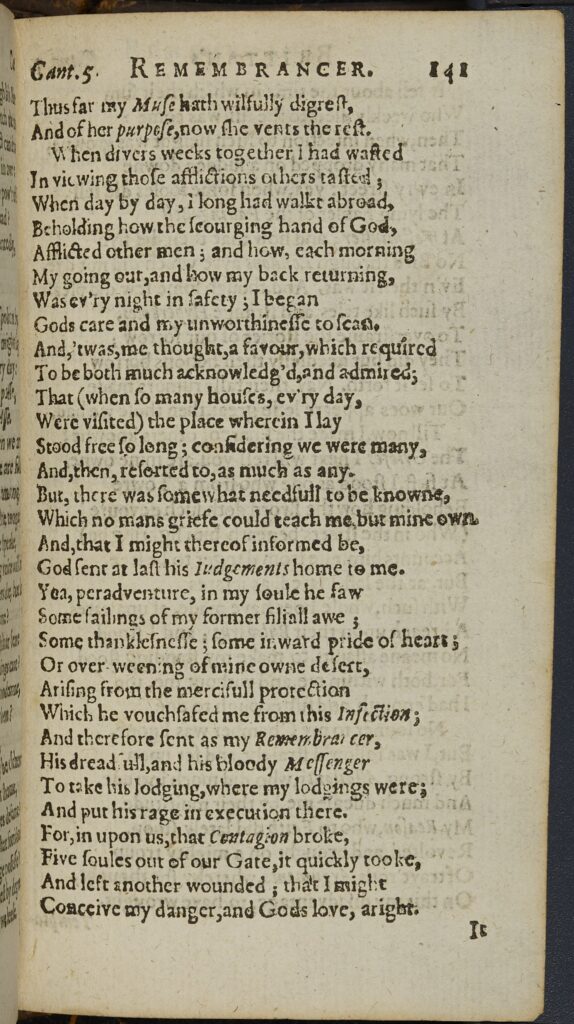

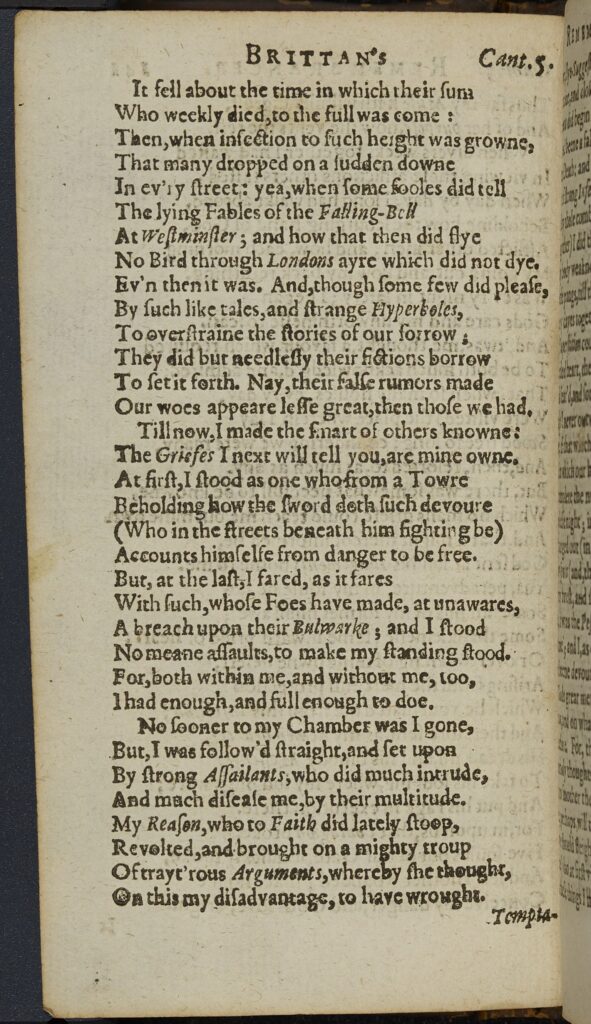

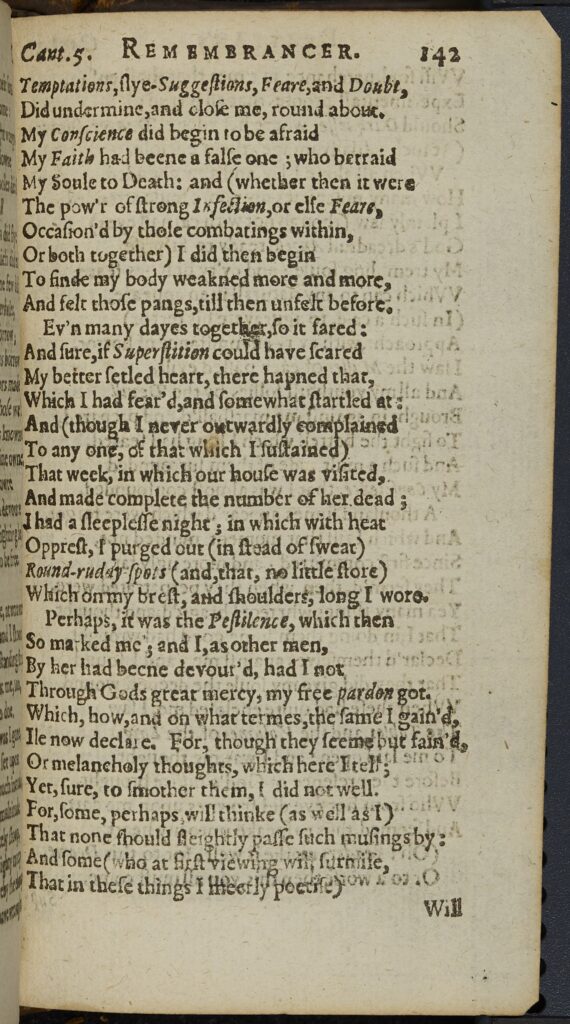

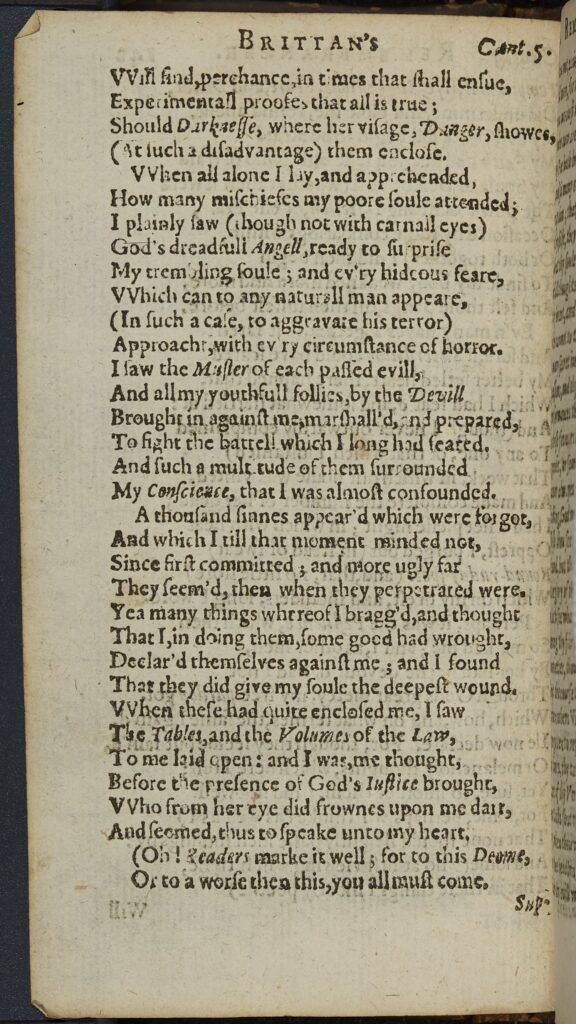

Britain’s Remembrancer

In this eight-canto poem, the English poet George Wither (1588–1667) acts as the nation’s ‘remembrancer’, recalling in vivid detail the 1625 plague epidemic.

First presented as a new year’s gift to Charles I in 1626, the poem recalls how, ‘when infection to such height was growne’, ‘many dropped on a sudden downe / In ev’ry street’.

At the height of his own fear at the spread of plague, Wither reflected on his many sins, ‘which I till that moment minded not’, aware that ‘God’s Justice’ might be on its way to him.

Magdalen College Library, Magd.Wither.G.8

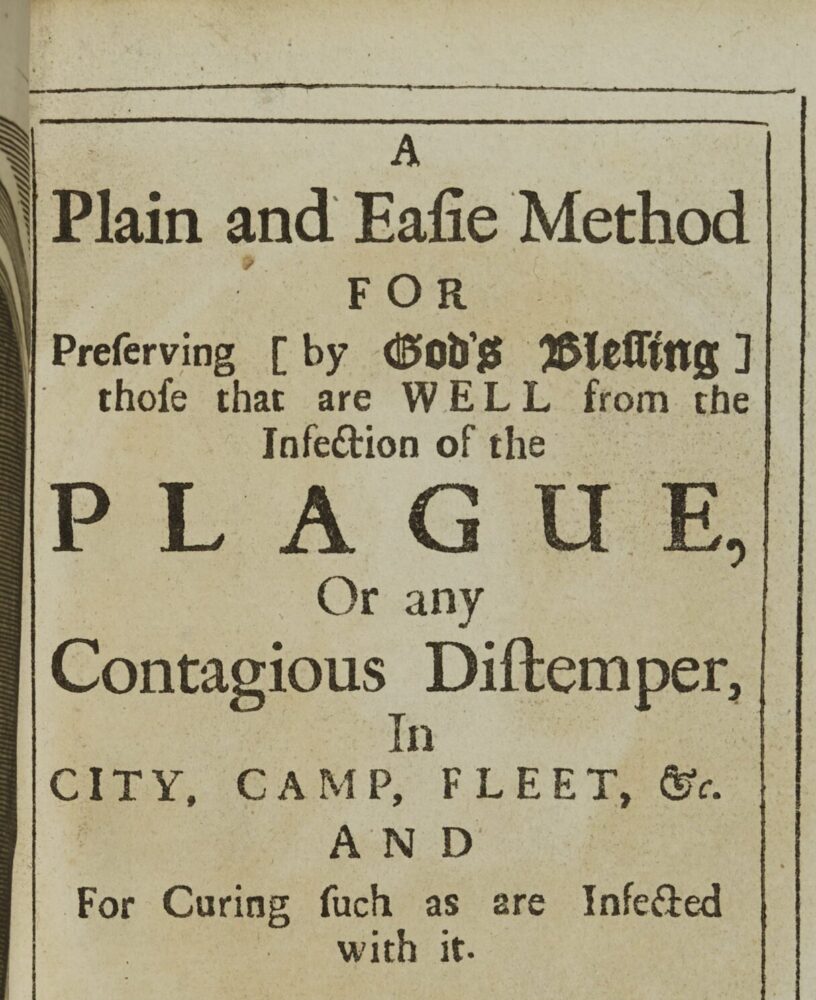

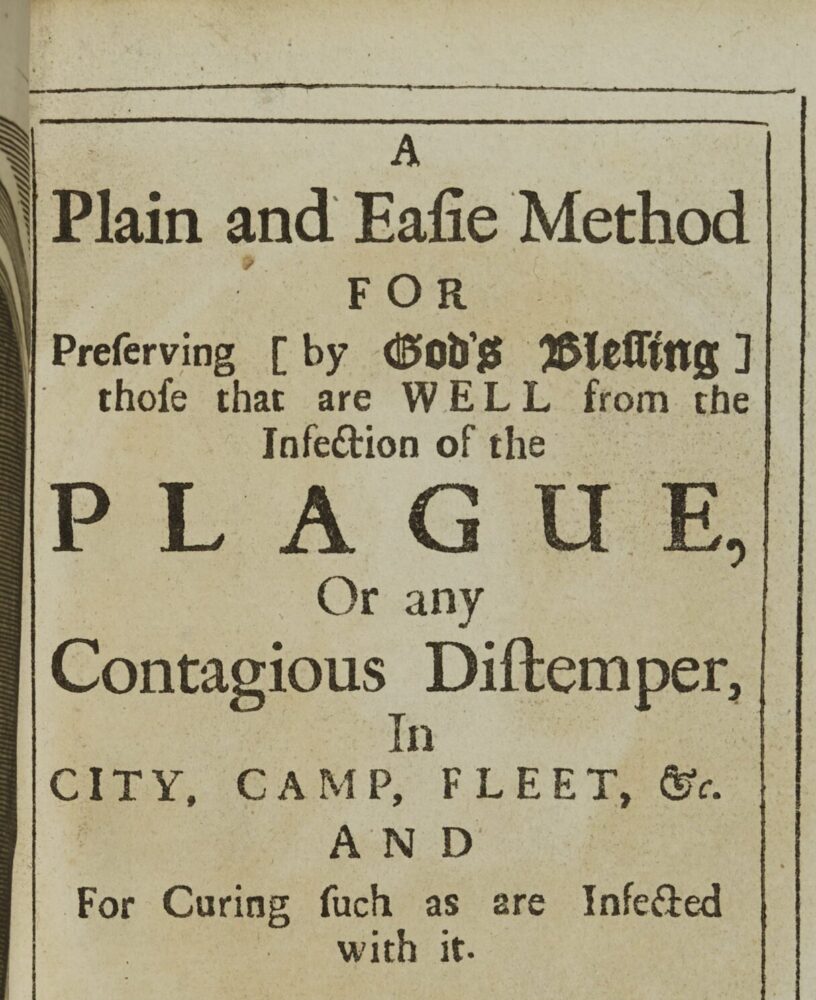

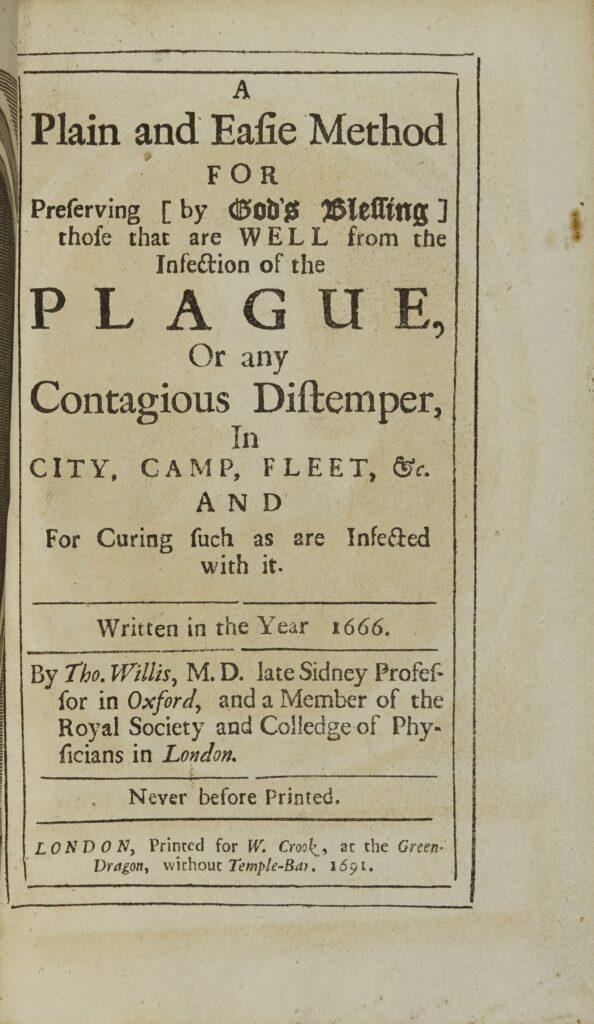

Plague Remedies

Thomas Willis (1621–75) was one of the most successful physicians working in mid-17th century Oxford. This pamphlet contains Willis’s recommendations for avoiding infection from plague.

One of his ‘potions’ involved making an ‘anti-pestilential vinegar’ from various roots, leaves, and flowers, and mixing it with ‘Venice Treacle’.

Willis knew that during epidemics it could be difficult to book a consultation with a doctor. He wrote this pamphlet so that everyone, rich or poor, would have to hand ‘Remedies against that Contagious Disease’.

Magdalen College Library, q.2.29

A Discourse on the Plague

The London physician Richard Mead (1673–1754) was an advisor to the Privy Council on the management of epidemics. He argued that plague was caused by infected air, infected persons, and the transportation of goods from infected regions.

In this book, which was first published at the request of the state, Mead advocated the quarantining of ships that arrived on English shores, as well as the quarantining of houses in which infected individuals resided.

His advice was incorporated into the new Quarantine Act of 1721.

Magdalen College Library, r.3.4